By Lilian DAVIN, Chief Executive Officer of CODA Systèmes

WHAT IS INDUSTRIAL VISION ?

In a cosmetics factory, thousands of metal boxes glide every hour on a conveyor. Each one must be flawless: no scratches, no dents, no surface defects. But who can judge at such a pace ?

Certainly not the human eye, too slow, too fallible, nor simple mechanical sensors. This is where industrial vision comes into play: an artificial eye, capable of detecting the slightest imperfection in real time (Figure 1). Wikipedia defines it as "the application of computer vision to industrial production and research fields." Specifically, it involves cameras paired with algorithms, capable of seeing, analyzing, and deciding. Quality control is its primary domain, but its range of applications is much broader: robot guidance, process assistance, traceability. I will focus here on the heart of the matter: automated inspection.

Born in the 1980s, driven by pioneers like Keyence (Japan), Cognex (United States), and Matrox (Canada), industrial vision was initially a technology for engineers by engineers. It quietly settled into workshops before experiencing a true revolution in the 2010s: the democratization of sensors, the rise of software libraries, and the spread of standards. Then, a few years ago, another revolution burst onto the factory scene: Artificial Intelligence. With it came a wave of hopes, promises, but also fears, debates, and sensational headlines in the press.

DECADES OF "RULE-BASED" ALGORITHMS

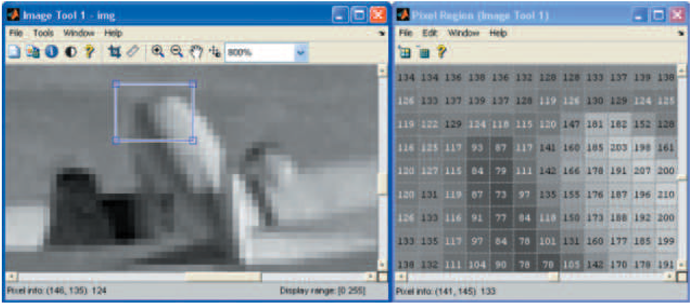

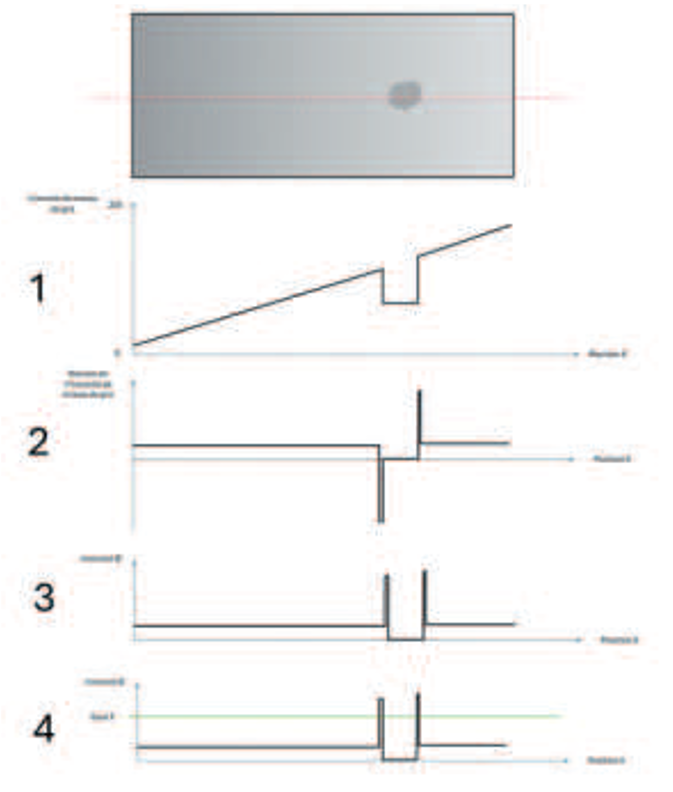

To understand what is happening today, we need to go back to the fundamentals. A "classic" 2D camera is made up of a photosensitive sensor (CMOS or CCD) divided into millions of receptors: the pixels. Each measures the light received and returns a value between 0 (black) and 255 (white). An image is therefore nothing more than a vast array of numbers: five million for a 5-megapixel black and white camera, for example (Figure 2).

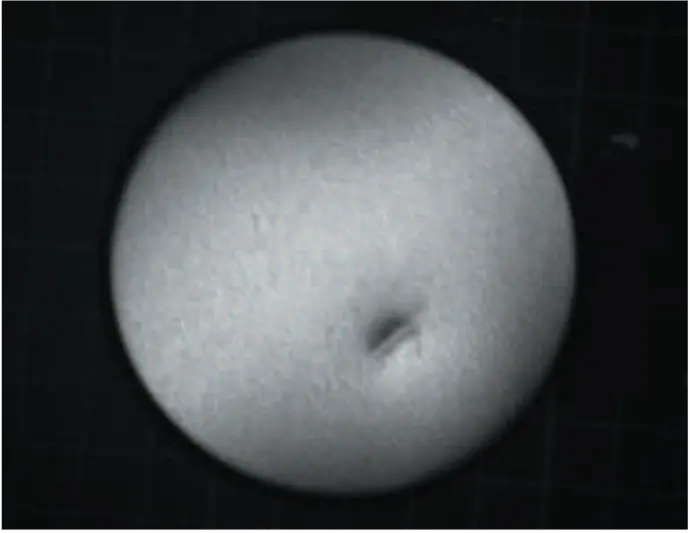

This is our raw material. The next step is to analyze it. Engineers have, from the very beginning, developed deterministic algorithms, or rule-based ones. They can be categorized into two families: • those that produce another image (filters, transformations), • and those that produce a usable measurement, referred to as "vision tools" (defect size, distance measurement, OK/NON-OK verdict). Let's take a concrete case: detecting a shock on a metal box (Figure 3).

The "blob" method

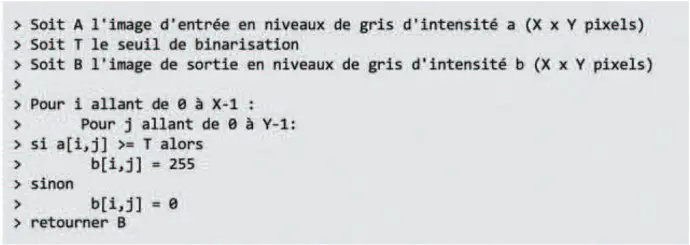

The oldest and simplest technique is to binarize the image. A threshold is chosen, and all brighter pixels become white (255), while all others become black (0). The result is a simplified image, black on white, where the defect is clearly visible.

The binarization algorithm resembles the basic sequence below :

And our image has become this one :

We can see our flaw very clearly, black on a white background. A few reflections on the edges prevent us from having a perfect white disc, but we will come back to it.

It remains to group the black pixels into an "aggregate" (blob). Each pixel is compared to its eight neighboring pixels. If some of them are black, they merge. And little by little, the defect takes shape. As a result, we obtain a multitude of information: number of aggregates, position, size, perimeter, orientation, etc. Enough to decide whether the part is compliant or not.

In our case, we obtain the results shown in Figure 5.

Simple, rational, explainable. But fragile. Because the threshold is fixed: if the lighting changes, if the background becomes more complex, everything collapses.

It is still possible to make this threshold dynamic, by taking, for example, the average intensity of the image (or a region), the median intensity, or even its own calculation as the threshold. It is sometimes referred to as "adaptive blob" or "dynamic blob."

However, there are countless cases that will pose problems for this method, whose simplicity quickly becomes its limiting factor.

Contrast detection

To overcome these limitations, other approaches have emerged. One of the most robust involves detecting local variations in gray levels: contrast. Here again, the defect stands out, but this time without relying on a single threshold. The principle is quite simple: we use the local variation in gray levels to detect abrupt changes, which correspond to the edges of our defect. The steps are as follows (Figure 6):

- We visualize the variation of gray level intensity along a line (illustrated by the red line). In this example with a gradient background, it is very easy to see how difficult it is to set a fixed threshold.

- We plot the derivative of this curve, representing the variations of these shades of gray.

- We deduce the absolute value, and we normalize.

- We can then set a threshold on this curve. The intersections between the threshold and the curve correspond to the outline of the defect.

And here is the result on our box

These methods (blob, contrast, and many others) constitute a powerful arsenal still in use today. Their strength: they are based on physical, rational, and traceable rules. Their weakness: they require specialized expertise to be effectively configured and combined.

THE ARRIVAL OF DEEP LEARNING

Then Artificial Intelligence knocked on the door of the workshops. Or more precisely: Deep Learning, or "Deep Learning."

Before going any further, let's clear up a common confusion. AI is not an ideology. Nor a cure-all. It is a tool. Like a knife, an internet browser, or a yogurt maker. AI can be useful, powerful, but it must be handled with discernment. Asking the question "Are you for or against AI?" makes as much sense as asking "Are you for or against knives?". You would be quite puzzled. It all depends on the context, the use, the intention. And let's not forget one obvious thing: a tool does not operate on its own. A yogurt maker, no matter how sophisticated, never makes good yogurt without someone who knows how to use it.

In industrial vision, AI often takes the form of convolutional neural networks applied to image classification. The idea is to show the model a multitude of examples until it learns to distinguish the good from the bad.

Imagine a pegboard, like in the game of the fakir. A ball (or an image) falls from slot to slot, bouncing chaotically, before landing in a numbered box. At first, everything is random. But after many iterations, the network adjusts its "pegs" (the internal coefficients), until the "good" balls fall into the OK box, and the others into NON-OK.

The learning method follows two main schools of thought:

- Supervised: we provide the already labeled images (OK/NOT OK). The model learns to reproduce these decisions.

- Unsupervised: we let the algorithm run without labels. It groups images into families, sometimes discovering new anomalies that we hadn't anticipated.

In practice, the industry mainly uses supervised learning, as companies already have classified defect libraries. However, unsupervised learning opens up fascinating perspectives: detecting defects never encountered before, the total unknown. (In simple terms: AI that tells you "I don't know what this is, but it doesn't resemble anything known").

Whatever learning method is used, the goal is that AI can detect defects, often with an excellent success rate. However, this process is not without significant constraints.

First of all, to achieve a satisfactory result, it is necessary to feed the AI a significant amount of images that are representative of the client's needs. Therefore, it is essential to undergo a long training phase before launching the system into production; otherwise, the AI may, for example, overlook a gigantic defect that is completely absent from its training cycle.

Next, the model does make decisions, but without explaining why. Its decisions are not based on physical rules or thresholds, but on adjustments of invisible coefficients. How can we explain that all my marbles (or images) of "camels" fall into the "camels" category? Because it clearly has four long legs, a hump on its back, and a caramel complexion? Absolutely not. But rather because the nails (coefficients) are positioned in such a way that this is the case every time. Understanding this functioning is both understanding the basis of Deep Learning and why AI differs completely from the functioning of our human brain.

Finally, learning is an energy-intensive process, and it is common to use high-performance machines remotely (in the cloud) to carry it out. This outsourcing of the training process can be a significant barrier for companies that want total control over their data and infallible privacy.

The trend for 2025: removing technological barriers

Transfer learning: cheat a little

As mentioned earlier, it often takes tens of thousands of images to train a model. Thanks to transfer learning, we start with a network that has already been trained on millions of generic images, and then we adapt it to our industrial application.

Result: a few hundred industrial images may be enough to build an effective model. And above all: saving time, energy, and avoiding turning the factory into a learning laboratory for months.

Explainability: the key to success

Major problem: AI cannot explain its decisions. However, there are techniques to "open the black box." For example, some models highlight the areas of the image that influenced the decision. Specifically, we can tell the client: "The part was rejected because the algorithm detected an anomaly here."

Other approaches seek to analyze the internal activity of neural networks: it is observed that certain layers of neurons respond more to specific shapes, textures, or patterns. In animal classification, for example, a group of neurons may be very sensitive to stripes (thus helping to identify a tiger).

It’s not perfect yet, but it’s a step towards the essential: trust.

Edge Learning: learning and deciding on-site

Imagine this: instead of sending each photo of your can to a server in California to check if it has a scratch, the camera processes the information directly on-site. This is Edge Learning: intelligence is embedded in the machine itself, whether it's the camera, the robot, or the small PC mounted on the side of the conveyor. The result: no time wasted, no reliance on the network, no risk of your industrial data wandering in the cloud. The AI makes its decision in milliseconds, right where it matters: at the edge of the production line. And sometimes, it can even continue to "learn" locally, adapting to real-world conditions (temperature, vibrations, dust, ambient lighting).

When AI meets rule-based: an effective duo

If we want to simplify, rule-based algorithms are rational but limited, while neural networks are adaptive but still mysterious. In reality, however, the two make an excellent duo when combined intelligently. AI can, for example, handle untangling a complicated image (noise, reflections, textures), and then pass the baton to the good old deterministic tools for precise measurements, thresholds, and the final verdict.

It’s the perfect complement: one paves the way, the other locks in the decision. Like in any good duo from classic cop shows, one is intuitive and a bit crazy, the other is methodical and straight-laced… and together, they always catch the flaw.

The aesthetic, playground of AI

Where AI becomes essential is in the detection of so-called "aesthetic" defects. Because even humans hesitate. One day a client told me: "This logo defect on this lipstick is too big, it should be classified as a bad piece, but since it's in the curve of the S, and... but if... you see... aesthetically it works." How do you translate this subjective judgment into binary rules? Should I now teach a robot the art and meaning of aesthetics? Impossible. But by showing the model a large number of examples validated or rejected by human experience, it can learn this nuance.

AI proves to be valuable where rules fall short: detection on complex backgrounds, texture defects, unreadable characters, and blurred aesthetics.

But it raises an essential question: trust. In nuclear energy, automotive, or aerospace, one cannot settle for an opaque verdict. Without explanation, there is no traceability. And without traceability, there is no progress.

THE STRATEGIC ISSUES

Artificial intelligence fascinates, but the industry demands more than fascination: it requires meaning, concreteness, and reliability. As we have seen, AI is a tool. It is a powerful and imperfect tool, capable of transforming our processes, but also raising questions. And in the rigorous and rational world of industry and quality control, the inexplicable has no place. We must understand why an AI decides, why it rejects, why it validates. Without explanation, there is no trust. Without trust, there are no real advancements.

Let's focus on what really works, that is, what meets the actual requirements of industry professionals, and especially on what we master. In industrial vision, the solution to a project is sometimes a cutting-edge AI that tackles a previously inaccessible challenge, and sometimes it's an image processing algorithm from an old library from the 90s. And that's OK. So obviously, it won't fit into the current boxes of European grants or investors, but it's always the results from the field that matter and that allow for impact.

We sometimes hear clients say, "We want to implement AI!" As if AI were a magic recipe that you sprinkle on the process to make it instantly intelligent. But AI is anything but a sprinkle of herbs: it doesn't just appear randomly. Sometimes it's the solution, sometimes it's not. And that's precisely where the experience and skills of industrial vision experts come into play. Because before adding AI, it's better to ensure that the dish really needs it. And if that's the case and AI is the solution, then let's maintain the same level of expectation for the result.

At CODA Systèmes, we adhere to three simple principles:

1. Pragmatism

The right solution is the one that works, not the one that shines. Cutting-edge AI can solve unprecedented problems, but sometimes the best answer is a robust, proven image processing technique that is perfectly sufficient.

2. Clarity

We refuse mystery. A technology has value only if it is understood. That’s why we train our clients: so that every industrialist becomes the master of their tools, and not the other way around.

3. Global vision

An automated quality control project is not limited to the choice of a specific algorithm used. It is essential to understand the complete needs of the client, the reasons why they want to implement these controls, the manufacturing process of the product, as well as the production environment and its constraints such as temperature, vibrations, dust, and stray lighting. At CODA, we strive to engage in extensive discussions with the client, analyze the entirety of the project, conduct a feasibility study under real production conditions, and propose a turnkey solution tailored to their needs.

CONCLUSION

The industrial vision, born from simple and precise rules, is now enriched by the promises of AI. But between fascination and skepticism, the essential remains: to choose the right tool, understand its decisions, and keep the human at the center of the process.

Furthermore, Europe should not be content with importing opaque models from elsewhere. Alternatives exist: explainable AI, Edge Learning, frugal AI. Let’s support them. Because in this field as well, independence is a condition for mastery.

In conclusion, the industry does not need illusions, but solutions. And perhaps that is, ultimately, the best definition of applied AI: a powerful tool, provided it is mastered.